Quality

In contrast to other years and the other sections in this report, our reporting on quality covers a period of five years.

The reason is that in the period 2019–2024, funds were spent that derived from the agreements made in April 2018 known as ‘Investing in the Quality of Education, Quality Agreements 2019–2024’.

The reporting in this section was prepared using the mandatory frameworks in those agreements. Outcomes and changes due to revised policies or unforeseen circumstances are discussed. These include the effects of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021.

This report effectively builds on the 2021 annual report. Progress across multiple years was also shared in that report.

Introduction

Between 2019 and 2024, the Quality Agreement funds made a major contribution to improving educational quality in many Erasmus University Rotterdam (EUR) Bachelor’s and Master’s programmes and had an impact on students and lecturers. The improvements came about through programmes. Three of these programmes were implemented at the decentralised level by the faculties, while the other three were implemented at the central level. The improvements were brought together in the Community for Learning & Innovation (CLI), where results were shared in learning communities and colleagues learned together. By conducting a comprehensive midterm review with the learning communities (2021/2022) and translating the outcomes into an updated educational vision, key insights were embedded for the long term. This was done in close collaboration with the University Council. Below is an overview of the improvements that were made.

Impact-driven education and skills training

Until 2019, education mainly focused on the priorities of internationalisation and academic success (Nominal is Normal, or N=N) as part of standard academic education. In 2024, education was increasingly about training students for a future where they will face challenges we cannot yet imagine. The academically trained professionals of the future will need a different and broader skillset to tackle these challenges and contribute to complex transitions. Broader skills training will enable students to engage with others on an equal footing, to identify and help solve key challenges. Between 2019 and 2024, students in all Bachelor’s programmes were given wider opportunities to work on ‘real-time’ or realistic outside world issues, challenging them to come up with approaches that contribute to understanding problems such as social inequality or inadequate access to health care. Personal and professional skills training continued to be developed in almost every Bachelor’s programme.

Lecturer professionalisation

Before 2019, in the area of education, investments in lecturer training and qualifications were made based on the nationwide agreements in place at that time (relating to the UTQ and STQ). The ambition in 2019 was to alleviate the workloads of academic lecturers, thus reducing work-related stress and improving the quality of teaching. In 2024, lecturer teams at EUR were strengthened by the arrival of education specialists known as ‘learning innovators’, who help improve how teaching is organised. A small-scale approach was promoted by the use of additional lecturers, student assistants, tutors and mentors. A training programme was developed for tutors, to better maintain the quality of their work. Lecturers can carry out improvement projects and conduct related research through fellowships. This ensures that innovation is informed by evidence. Lecturers receive 0.2 FTE of compensation for fellowship projects. The CLI brings together lecturers and learning innovators to exchange and develop knowledge.

Hybrid and online education

In 2019, lecturers cautiously experimented with online teaching in lectures by ‘flipping the classroom’. This involved integrating hybrid and online forms of teaching over a series of lectures. The improvement programme initially focused on developing teaching materials and opportunities for online and in-person interactions using traditional, location-based methods. In 2019, an ambition was expressed to speed up future education: making teaching more flexible through the use of online and hybrid teaching. Then came Covid. During the pandemic, the faculties were allowed to use all their resources to provide fully online education. After the pandemic, the development of hybrid and online education continued. This was done within programmes and by documenting ‘lessons learned’ in the Community of Practice. The Covid pandemic accelerated the process of online and hybrid working, and has now given rise to an important follow-up task: How can we use EdTech and Artificial Intelligence to future-proof education?

Student success and student wellbeing

In 2019, the emphasis was on academic success and measures aimed at ensuring that students would not be delayed in their studies. EUR is still committed to those goals, but a broader approach has also been developed to improve students’ mental wellbeing. The emphasis is on prevention. The provision of information has improved, and there are accessible facilities that invite students to seek help when needed. A ‘student living room’ has been created, where trained student hosts are available every day. Awareness-raising campaigns and student wellbeing weeks are organised each year to encourage discussion around student wellbeing. Additional psychologists have been appointed (including online psychologists) and student counsellors meet in an interfaculty community aimed at improving integrated care within the university.

Learning culture

Most plans were drawn up in faculties and in close consultation with participation bodies, which fits with the decentralised nature of EUR. Conversations around the question ‘What is educational quality?’ were therefore held with those directly involved, at the coalface. In addition, professionals and students learned in groups known as ‘Communities of Practice’ and collectively discussed curriculum developments. The lessons went beyond exchanging information and finding inspiration. In the midterm review, conclusions were drawn based on dialogue and follow-up goals were formulated. In this way, the Quality Agreement funds contributed to a learning culture, making a recognisable contribution to the constant improvement of the quality of education at EUR: ‘Being an Erasmian; making a positive societal impact’.

Financial reporting 2019–2024

By the end of 2024, EUR had spent all available funds. Some of the funds that had been earmarked for 2022–2024 were spent earlier, to accelerate the capacity for innovation. This approach proved a success, as evidenced by the speed with which improvements were made and what was achieved by the end of the period.

EUR has an internal system to distribute financial resources to the faculties based on student numbers. In addition, funds are set aside at the central level of the university for investments that support collective, interfaculty facilities and for work to define EUR’s profile. This distribution was applied to the Quality Agreement funds, as agreed with the participation bodies in 2019. The financial reporting in this section is therefore divided into a faculty part and a part dealing with programmes organised at the institution level.

Available funds (2019–2024), x €1,000.

| Available funds and spending (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Agreement funds – central government grant | 6,138 | 7,401 | 12,845 | 16,972 | 17,764 | 22,180 | 83,300 |

| EUR funds (committed) | 4,208 | 5,193 | 1,739 | 286 | 121 | 121 | 11,668 |

| Total available funds | 10,346 | 12,594 | 14,584 | 17,258 | 17,885 | 22,301 | 94,968 |

Overall spending overview

Table 3 provides an overview of the funds that were available to implement innovations and improvements. In addition to the government funding, in the early years, the faculties were able to apply for extra money from EUR’s reserves. This allowed us to speed up the quality and innovation programme. It worked well. Table 3 shows how much we received, along with the extra funds contributed by EUR. Table 4 shows that all funds received from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, ‘the Ministry’) were fully spent. The table provides an insight into how much of the university’s own funds were spent during the period.

In the period 2019–2021, a fixed amount of Quality Agreement funds was available for faculties and programmes, based on the central government grant. However, student numbers increased during this period. Following the 2022 midterm review, the calculations were corrected and the participation bodies were able to help determine how the additional funds (€2.985 million) would be spent. Additional meetings with the participation bodies were held to discuss this matter.

Overview of spending of funds by EUR (2019–2024), x €1,000.

| Spending (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending of Quality Agreement funds | 6,138 | 7,401 | 12,845 | 16,972 | 17,764 | 22,180 | 83,300 |

| Spending of other funds | 1,518 | 6,277 | 1,137 | -2,985 | -16 | 316 | 6,246 |

| Total spending | 7,656 | 13,678 | 13,982 | 13,987 | 17,748 | 22,496 | 89,546 |

Roughly two-thirds of the available Quality Agreement funds were distributed among the faculties, in accordance with the aforementioned internal arrangements. Table 5 shows how the funds were spent by faculty.

Spending of Quality Agreement funds by faculty 2019–2024 x €1,000

| Spending 2019–2024 (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMC | 310 | 1,964 | 1,727 | 773 | 595 | 2,194 | 7,562 |

| ESE | 1,108 | 1,387 | 1,787 | 1,777 | 2,276 | 2,693 | 11,029 |

| ESHPM | 304 | 358 | 353 | 439 | 391 | 621 | 2,466 |

| ESL | 1,239 | 1,786 | 1,818 | 1,587 | 1,961 | 2,73 | 11,122 |

| ESSB | 1,083 | 1,938 | 1,919 | 1,99 | 2,128 | 2,52 | 11,579 |

| ESHCC | 283 | 451 | 445 | 361 | 333 | 665 | 2,538 |

| RSM | 1,469 | 2,02 | 1,914 | 1,919 | 2,142 | 2,685 | 12,149 |

| ESPHIL | 209 | 301 | 266 | 273 | 229 | 507 | 1,785 |

| 6,006 | 10,205 | 10,229 | 9,120 | 10,054 | 14,616 | 60,23 | |

The above table shows two larger changes. During the period, changes occurred in two faculties: Erasmus University Medical Centre (Erasmus MC) and Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication (ESHCC). In 2019, Erasmus MC’s improvement agenda was developed for two years, as reported when the plans were submitted. Setting up the second round of the improvement agenda led to a fluctuation in spending of the Quality Agreements funds (although EUR funds to support educational quality continued). ESHCC decided to review its improvement agenda. Both Erasmus MC and EHCC initially used a method that allowed lecturers to submit proposals directly. Both faculties later switched to a method similar to the one used by other faculties, by which decisions on multi-year development plans were made in conjunction with degree programmes and teams. The ‘Innovation Hubs’ that initially proposed projects by period became coordination points where funds were efficiently distributed based on a common improvement agenda.

Around a third of the Quality Agreement funds were spent as planned in multi-faculty initiatives: the Community for Learning & Innovation (CLI) and three additional programmes designed in conjunction with the University Council: Erasmus X, Impact at the Core and Student Wellbeing. Table 6 shows the spending on these programmes.

Overview of spending of Quality Agreement funds including other central programmes, x €1,000.

| Central programmes | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erasmus X | 53 | 859 | 1,006 | 1,264 | 2,164 | 2,071 | 7,417 |

| Impact at the Core | - | 317 | 923 | 1,05 | 1,785 | 2,029 | 6,104 |

| Wellbeing | 76 | 459 | 480 | 508 | 751 | 1,089 | 3,363 |

| CLI | 1,521 | 1,838 | 1,343 | 2,045 | 2,847 | 2,837 | 12,431 |

| Central programmes | 1,65 | 3,473 | 3,752 | 4,867 | 7,547 | 8,026 | 29,315 |

The Erasmus X and Impact at the Core programmes received maximum budgets of €1.3 million (Erasmus X) and €1.5 million (Impact at the Core). Both programmes worked according to a model of experimentation followed by scaling-up in the faculties. Any money not spent in the start-up period (up to 2021) was allowed to be carried over to a subsequent year. All annual budgets, plans and results were discussed in detail with the University Council’s HOKA committee. The University Council ultimately approved the annual budgets.

Overview of overall spending by Ministry theme

The Quality Agreement funds are linked to mandatory themes in the framework. The table below shows the spending on each theme set by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

Overview of investments by Quality Agreement theme, x €1,000.

| Ministry themes (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Small-scale and intensive | 2,279 | 3,346 | 3,932 | 3,994 | 4,014 | 5,379 | 22,943 |

| 2 More and better guidance | 2,281 | 4,028 | 3,178 | 2,416 | 3,289 | 4,724 | 19,916 |

| 3 Academic success | 22 | 50 | 31 | - | 3 | 26 | 132 |

| 4 Educational differentiation | 2,503 | 4,762 | 5,868 | 6,49 | 8,800 | 9,751 | 38,174 |

| 5 Teaching facilities | 151 | 659 | 77 | 105 | 138 | 1,082 | 2,211 |

| 6 Professionalisation/quality of lecturers | 420 | 834 | 896 | 982 | 1,503 | 1,534 | 6,169 |

| 7,656 | 13,678 | 13,982 | 13,987 | 17,748 | 22,496 | 89,546 |

EUR linked the spending of the funds based on the mandatory Ministry themes to its own themes, which were aligned with its educational vision and educational quality. The university’s educational vision is based on its mission. In designing a learning culture, the Quality Agreement funds from the Ministry were linked to themes recognised by the internal academic community and based on this mission-driven educational vision. These themes are explained below. The tables provide an overview of spending by theme.

Spending by EUR theme

| EUR themes (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Personal Professional Development | 2,825 | 3,741 | 3,805 | 3,155 | 3,654 | 5,177 | 22,357 |

| 2 Innovation Capacity | 2,086 | 3,191 | 3,763 | 3,617 | 4,201 | 5,262 | 22,12 |

| 3 Personal Learning Online Facilities | 1,095 | 3,274 | 2,662 | 2,288 | 2,124 | 3,859 | 15,3 |

| 4 Wellbeing | 76 | 459 | 480 | 568 | 918 | 1,224 | 3,725 |

| 5 Impact at the Core | 0 | 317 | 923 | 1,05 | 1,839 | 2,066 | 6,196 |

| 6 Erasmus X | 53 | 859 | 1,006 | 1,264 | 2,164 | 2,071 | 7,417 |

| 7. CLI | 1,521 | 1,838 | 1,343 | 2,045 | 2,847 | 2,837 | 12,431 |

| 7,656 | 13,678 | 13,982 | 13,987 | 17,748 | 22,496 | 89,546 |

Process design for monitoring of the Quality Agreements 2019–2024

Monitoring was performed in two ways. The faculties reported three times a year, based on the indicators listed in the table below. These reports were summarised in the annual report and discussed with the Supervisory Board and participation bodies at the central level.

The effects on educational quality were qualitatively identified in four learning communities known as ‘Communities of Practice’. There, professionals and students from the faculties learned together how educational quality had been improved. These learning communities were led by a scholar. By the end of 2021, all interim results had been discussed with stakeholders in dialogues. The aim was to give meaning to the outcomes through a narrative. The outcomes were recorded in a report entitled ‘Four Dialogues’, which was published in December 2021.

[1]Based on a review by an external panel, starting in 2022, there were discussions about whether changes needed to be made to the plans for 2022–2024. This process was designed in close consultation with the participation bodies.

Results for Personal and Professional Development of Students (Ministry Themes 1 & 2)

Overview of investments by faculties in Personal and Professional Development (Ministry Theme 1, Ministry Theme 2) x €1,000

| Faculty spending on Ministry Themes 1 & 2 (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMC | 120 | 539 | 630 | 15 | 58 | 335 | 1,697 |

| ESE | 559 | 785 | 948 | 975 | 969 | 1,338 | 5,573 |

| ESHCC | 244 | 308 | 303 | 283 | 152 | 419 | 1,709 |

| ESL | 742 | 935 | 855 | 746 | 1,04 | 1,604 | 5,921 |

| Esphil | 20 | 40 | 30 | 36 | 34 | 94 | 254 |

| RSM | 1,024 | 989 | 923 | 964 | 1,011 | 1,02 | 5,931 |

| ESSB | 116 | 146 | 117 | 136 | 389 | 368 | 1,271 |

| Grand Total | 2,825 | 3,741 | 3,805 | 3,155 | 3,654 | 5,177 | 22,357 |

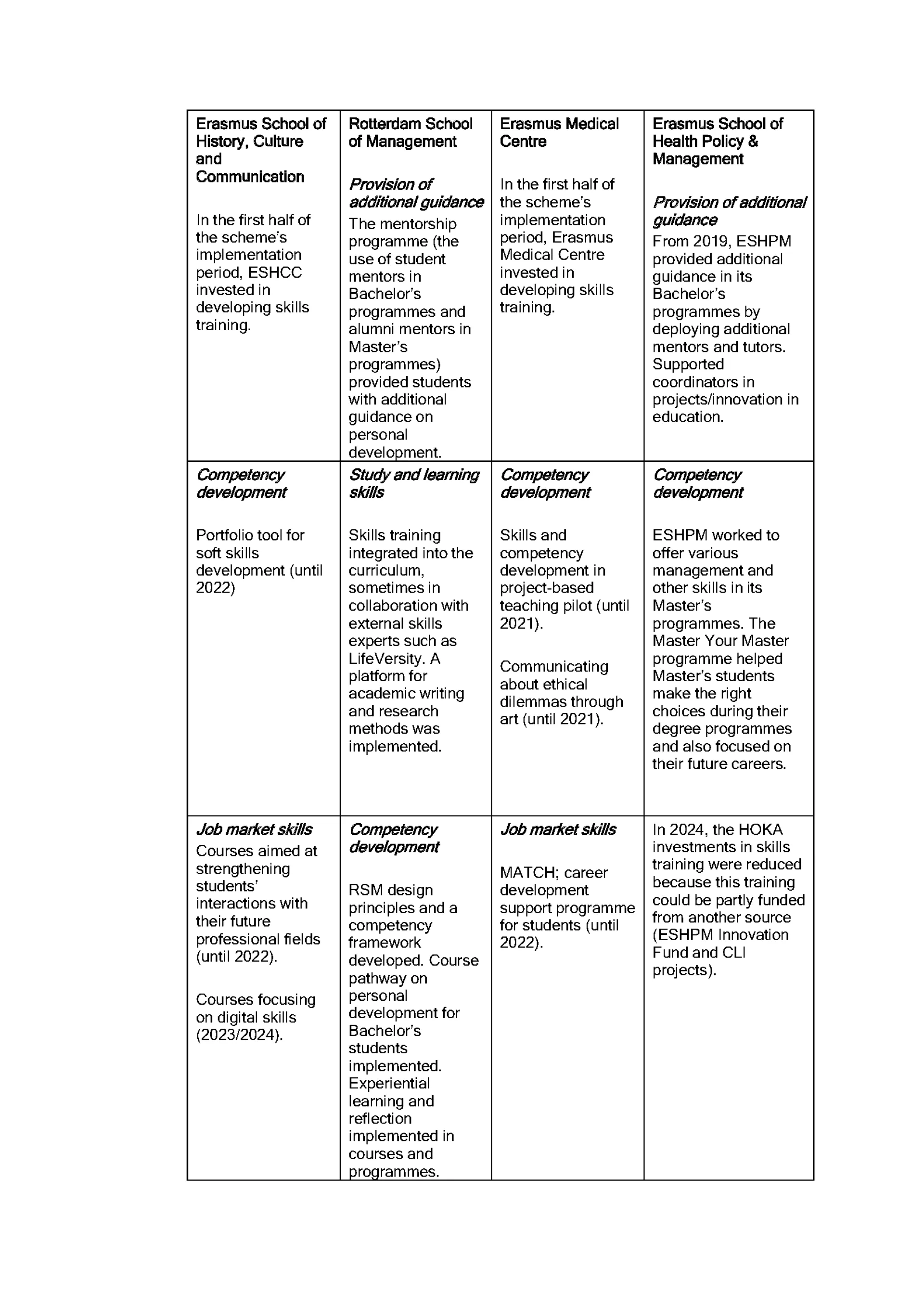

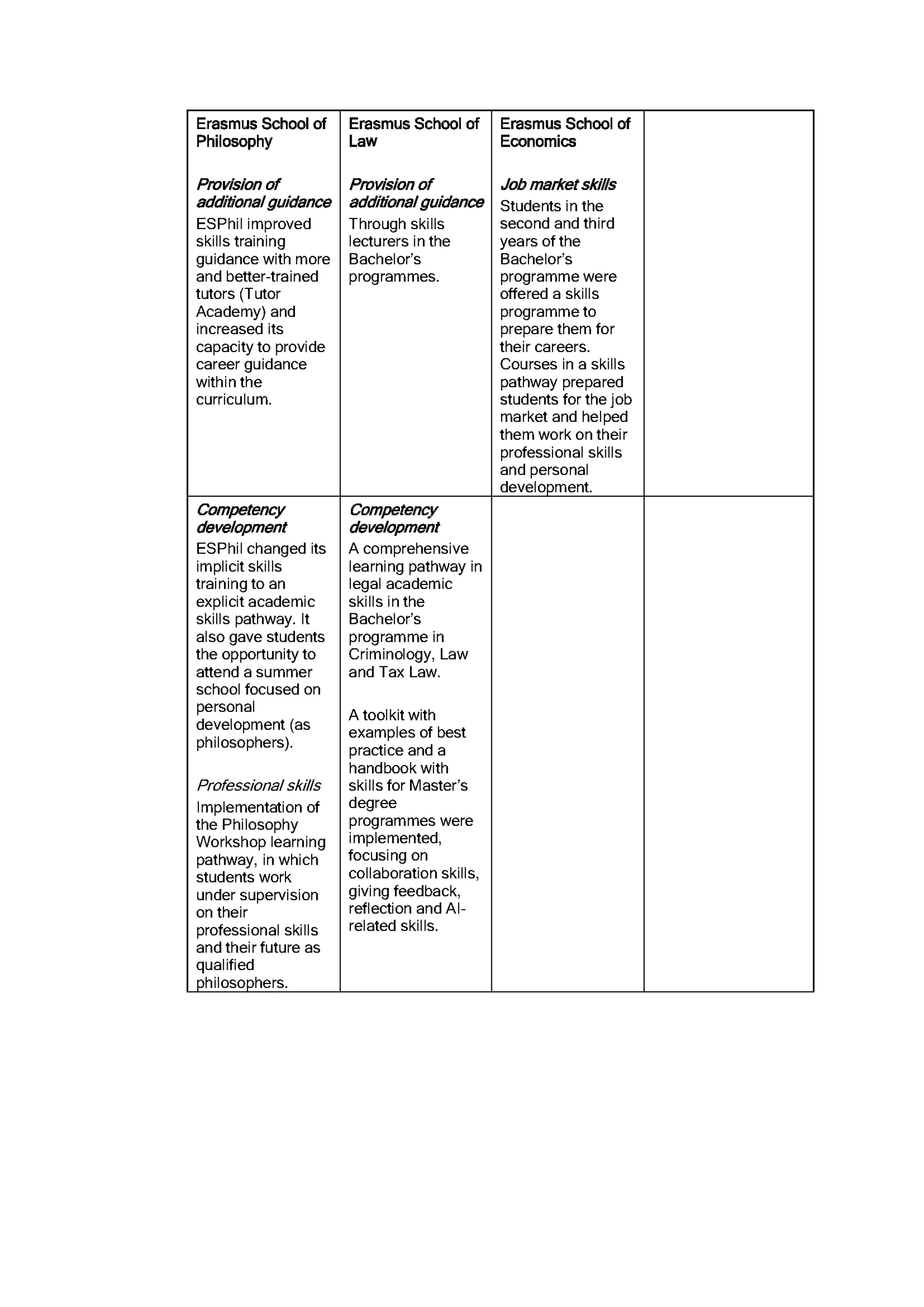

Personal and Professional Development objectives

The personal and professional development objectives for 2019–2024 were:

- Skills courses focusing on personal development and connection to careers and the job market.

- Additional guidance for students.

The faculties drew up and implemented the associated plans.

The theme of ‘personal and professional development of students’ was implemented at the decentralised level by the faculties, in consultation with their faculty participation councils. This allowed each faculty to have a different emphasis. RSM and ESL focused on faculty developments. For both faculties, reviews of their Bachelor’s programmes in particular prompted them to invest more in feedback on personal development (RSM) and on developing the specific skills required for final projects and future careers (ESL). The other faculties invested in improvement goals within the framework of the university’s mission and educational vision.

What were the results?

In 2019, training in skills (study and learning skills, career preparation, competency development and academic skills) was implicitly offered within discipline courses in most faculties. Other than in the Erasmus School of Social Sciences and Behaviour (ESSB), there were no explicit learning pathways for skills training. In 2024, all faculties had a learning pathway for academic skills, or offered multiple skills courses as a structural component of their Bachelor’s programmes. The skills are explained in the appended Diagram 7. Additional lecturers and mentors were used to provide better guidance for students in this area. The structural focus on skills training is rooted in the educational vision. Skills training contributes to student resilience, learning skills and the professional skills needed to solve complex challenges in collaboration with others as academic professionals.

Following the midterm review of the Quality Agreements, this theme led to adjustments to EUR’s educational vision in 2023. Those adjustments will continue to contribute to the development and quality of education in the years ahead.

Our Erasmian education develops students’ capacity. We focus on student success. This involves promoting success in terms of academic achievements as well as students’ personal development and wellbeing. We support students to develop a personal and professional (academic) identity and expect students to take responsibility for their learning process. They can co-create knowledge with partners from other disciplines and diverse cultural backgrounds, and can collaborate with partners in society. We teach students to think critically about their own assumptions and be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of those assumptions. They can build and maintain reciprocal relationships, understand the ‘other’ and contribute to a shared understanding and sustainable approaches to societal needs and urgent challenges.

Source: Educational vision 2023.

table 10 Information on the projects related to this theme.

Student Wellbeing 2019–2021 (Ministry Theme 2)

Investment of Quality Agreement funds in Student Wellbeing (central) 2019–2021 x €1,000.

| Spending on Wellbeing (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student support services and lecturers | - | 45 | 195 | 199 | 201 | 269 | 908 |

| Student Living Room | 1 | 57 | 82 | 103 | 155 | 140 | 537 |

| Mission and data | 75 | 331 | 114 | 122 | 134 | 134 | 910 |

| E-Platform and Helpline | - | 27 | 88 | 85 | 75 | 118 | 392 |

| Communication and Research | - | - | - | - | 64 | 262 | 327 |

| Caring Universities | - | - | - | - | - | 88 | 88 |

| Outdoor Living Room and Sports | - | - | - | - | 25 | 86 | 110 |

| Personal Support Hub | - | - | - | - | - | 90 | 90 |

| 76 | 459 | 480 | 508 | 751 | 1,089 | 3,363 |

Investment of Quality Agreement funds in Student Wellbeing (faculties) 2019–2021 x €1,000.

| Spending on Wellbeing by faculties (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESE | - | - | - | 60 | 166 | 34 | 261 |

| ESL | - | 101 | 101 | ||||

| 60 | 166 | 135 | 362 |

Student Wellbeing objectives (Ministry Theme 2)

EUR has been committed to the personal wellbeing and development of students since 2019, well before the introduction of the National Education Programme (Nationaal Programma Onderwijs, NPO) or the inclusion of the theme of Student Wellbeing in the new Administrative Agreement. Before 2019, the emphasis was on preventing study delays in the first year of Bachelor’s programmes and monitoring academic achievements in subsequent years. Since 2019, EUR has been committed to developing a vision and implementing measures for student success. The focus on academic achievement was retained, alongside a much broader examination of students’ competencies and skills to develop mental resilience. A university-wide innovation programme was launched, with the ambition of promoting student wellbeing across all faculties and curricula. Since 2023, the programme has worked on disseminating the results of academic research on the effects of the programme at the national level.

What were the results?

There is broad support in all faculties for the importance of student wellbeing. The focus on student wellbeing is rooted in the educational vision, and is thus embedded for years to come.

Our Erasmian education develops students’ capacity

We focus on student success. This involves promoting success in terms of academic achievements as well as students’ personal development and wellbeing.

Source: Educational vision 2023

Student Wellbeing Manifesto (2022)

All faculties endorsed a manifesto expressing commitment to normalising the conversation around mental wellbeing and providing timely and comprehensive support to students. This is done with interventions underpinned by academic research on their effectiveness.

Strengthening support for students (2020–2024)

Better information

A short animated video was created on how to keep your life in balance as a student and how to study with motivation. This video has been screened at the start of lectures since mid-2022. The video contains a link to a clear overview of EUR’s full range of support services. These include services aimed at prevention (such as workshops on dealing with stress or procrastination) as well as peer support and online coaching from a student psychologist or external professional.

The student living room

The student living room is an accessible, permanent, non-commercial place to socialise. The living room serves 22,000 students a year (an average of 90 per day), some of whom visit the living room multiple times. Hosts are present in the living room to give students information and refer them to internal and external resources if necessary.

Fresh Thoughts and online services

The online wellbeing platform for students had around 200,000 page visits in the period from 2021 to 2024. The peer-to-peer chat service Fresh Thoughts has been part of the online wellbeing platform since 2021. Student satisfaction is high.

Additional psychologists and online services

Following an internal investigation, an additional psychologist was appointed. In addition, online coaching was implemented and EUR joined Caring Universities. This initiative provides access to online mental health modules for students.

A GP clinic also opened near the campus in 2022 for students to visit.

Mission and Data (KPI)

From 2020 to 2023, student wellbeing was measured every year. EUR also participated in the nationwide Monitor on Mental Health and Substance Use (RIVM/Trimbos/GGD-GHOR) in 2022 and 2024. After 2024, the two monitors will alternate each year. The fourth EUR Student Wellbeing Monitor, conducted in 2023, showed that although there had been minor improvements in the percentage of students experiencing poor mental wellbeing, the overall situation remained concerning and was similar to the result from the third Monitor. It showed that 40% to 60% of students were struggling with mental health issues – mainly anxiety, depression, loneliness and burnout. The 2023 nationwide Monitor on Mental Health and Substance Use showed that EUR scored significantly more positively on mental health than other universities. However, the score for substance use was slightly more negative.

Investing in lecturers’ innovation capacity

Faculty and central investment of Quality Agreement funds in lecturers’ innovation capacity x €1,000.

| Ministry Theme 6 (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLI | 351 | 758 | 706 | 810 | 961 | 1,002 | 4,588 |

| EMC | - | - | 23 | 44 | 3 | 144 | 214 |

| ESE | - | - | - | - | 240 | 265 | 504 |

| ESHPM | - | - | - | - | 5 | 70 | 75 |

| IATC | - | - | 83 | 48 | 13 | 48 | 192 |

| RSM | - | - | - | 2 | 17 | 20 | 38 |

| ESSB | 69 | 76 | 84 | 78 | 119 | 132 | 558 |

| 420 | 834 | 896 | 982 | 1,50 | 1,53 | 6,17 |

Objectives for Investing in lecturers’ innovation capacity

Before 2019, lecturer training was offered as a comprehensive programme. Lecturers were individually responsible for the entire process, from design to implementation of their courses. The aim was to split up design and supervision tasks, thus allowing for more team-teaching.

What difference did the investment make?

Based on the mid-term review (2021/2022), the approach was incorporated in EUR’s educational vision, then developed into a supplementary policy framework:

EUR lecturers challenge themselves to use and develop up-to-date, effective and evidence-based approaches to teaching, study and assessment. At the education level, teaching frameworks challenge students to translate their knowledge into a critical understanding of urgent societal challenges. Thanks to their extensive repertoire of pedagogical and teaching skills, our lecturers are able to provide an inclusive and safe study landscape in which all students can achieve success and reach their full potential.

EUR lecturers often work in teams. Lecturers collaborate with mentors, tutors, coaches and/or educational innovators and other support staff, as well as with civil society partners.

Teaching teams are interested in students’ personal wellbeing and help students develop resilience and self-regulating professional and academic competencies as part of their academic, personal and professional identity. Source: Educational vision 2023

Was this ‘unbundling’, which was also included in the vision, achieved? The goals that were set during the process were. In 2024, lecturers were still in control of their own teaching, but the faculties had worked on ‘unbundling’ lecturers’ duties to reduce their workloads. Nevertheless, workloads remain high.

RSM, ESSB, ESPhil, ESHPM and ESE invested in additional tutors who had been better trained in a Tutor Academy. In addition, many faculties either appointed learning innovators (RSM, ESSB, ESL, ESE) or invested in coordination of curriculum coherence and development. Most faculties were satisfied with the deployment of learning innovation staff. Thanks in part to their efforts, innovations within projects were able to be better embedded at the curriculum level or used to support lecturers’ professional development. Learning innovators, as well as being educational developers, also helped deliver informal training, so lecturers could learn on the job.

In response to new policies around lecturer professionalisation, from 2023 onwards the faculties invested in additional activities in team-teaching and constructive alignment.

The Community for Learning & Innovation (CLI) was given centralised support to promote lecturers’ innovation capacity. The CLI developed a range of courses for lecturers to help them continually improve quality and innovation in their teaching. This also enabled them to constantly adapt to societal changes, new teaching insights based on academic research and new technological possibilities. Faculties with less capacity for learning innovation, due to their smaller size, were able to use the services of the CLI. All the sub-objectives set by the CLI and faculties for this purpose were achieved.

These included:

Microlabs

The goal was to develop 10 microlabs with a total of 1,000 participants by the end of 2024. Microlabs are short ‘how-to’ modules delivered by EUR lecturers on specific educational issues. A total of 24 microlabs were developed, in which a total of 2,383 lecturers participated. During the COVID crisis, additional training materials on online teaching and assessment were made available online. ‘TeachEUR’, an online design tool for lecturers, was also produced. Several interactive webinars were provided, such as the ‘Online interaction and tool experience’ and ‘Online assessment’. In 2020, 191 lecturers participated in these webinars.

Fellows: the lecturer as innovator

The target of twenty active fellows per year was more than achieved in all years, with numbers peaking towards thirty in most years. The only exception was 2019, when the programme had just started and there were nineteen fellows. Research by fellows mainly focused on skills training, blended, hybrid and online teaching, and student and lecturer motivation and wellbeing.

Project support

The CLI was tasked with supporting an average of fifty projects a year with additional learning innovation capacity. This was successful, after a start-up period for the first three years.

Personal and Online Learning (Ministry Themes 4 and 5)

Financial reporting on personal and online learning (x €1,000).

| Personal and Online Learning – Ministry Themes 4 and 5 (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLI | 351 | 758 | 706 | 810 | 961 | 1,002 | 4,588 |

| Faculties | 693 | 2,255 | 1,869 | 1,666 | 1,471 | 2,961 | 10,915 |

| 1,044 | 3,013 | 2,575 | 2,476 | 2,432 | 3,963 | 15,503 |

Financial reporting by faculties (x €1,000).

| Personal and Online Learning – CLI; Ministry Themes 4 & 5 (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational innovation projects | 677 | 430 | 228 | 352 | 953 | 884 | 3,524 |

| ErasmusU_Online projects | - | 74 | 361 | 452 | 312 | 1,199 | |

| 677 | 430 | 302 | 713 | 1,405 | 1,196 | 4,723 |

Objectives for Personal and online learning (Ministry Themes 4 and 5)

In 2019, the ‘Flipping the classroom’ programme was completed, with university-wide courses in a select number of degree programmes having been redesigned to incorporate digital online elements, such as the Master’s in Employment Law. After 2019, it was agreed with all faculties to establish a programme on personal and online learning. The objectives focused on revamping the online learning environment for students so that they were more personally challenged and education was more flexible. Innovations enabled students to a) learn off campus, in their own time; b) receive more and better feedback on the learning process; and c) ensure that teaching was adapted to their specific learning questions. ESSB appointed a learning innovation team focusing on online education. This team incorporated this innovation into the Psychology degree programme, among others.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, all teaching was delivered online. This was possible due to the commitment of learning innovation staff in the faculties, and with the CLI playing a major role. The CLI provided technical support, as well as numerous workshops, webinars and toolkits to help lecturers deliver their lessons online. This ultimately led to a new toolkit for lecturers, the refinement of several fully online programmes and the development of chatbot technology to give students better and faster feedback on frequently asked questions. These tools were mainly used in RSM.

The mid-term review led to the decision to provide primarily on-campus education. The aim was to use hybrid and online learning until 2030 to facilitate target groups who, for various reasons, are less able to participate in on-campus education.

What difference did the investment make?

Overall, all faculties adapted many of their courses, and four projects relating to assessment were successfully completed. The improved courses better matched students’ initial situations and motivation. The courses included features such as ‘serious gaming’ (ESHCC), adaptive modules (Erasmus MC) and making learning independent of time and location. The knowledge clips developed by the Faculty of Economics are an example of time and location-independent learning. Students prepare for tutorials at home. In addition, online tools are used to allow students to collaborate in simulations or case studies, including in interdisciplinary scenarios (ESPhil).

A broad-ranging midterm dialogue on hybrid, online and personalised learning was held in 2021. It showed that the role of online learning in the transfer of knowledge needed to be established, that knowledge must be applied to solve issues, and that students’ personal development needed attention. In this regard, it may be necessary to individualise education, but better thinking about how online teaching methods could contribute to better learning outcomes should be the top priority.

With help from the CLI, the ‘Hybrid and online learning’ programme continued, encompassing both an experiment in digital teaching methods in a fully online programme (not funded out of Quality Agreements funds) and the further development of microlabs, toolkits and events where lecturers could share their experiments. The conversation on digital teaching methods and assessment continued in a Community of Practice.

Impact learning (Ministry Theme 4)

Financial implementation of the Impact at the Core programme x €1,000.

| IATC (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact at the Core | - | 317 | 923 | 1,05 | 1,785 | 2,029 | 6,104 |

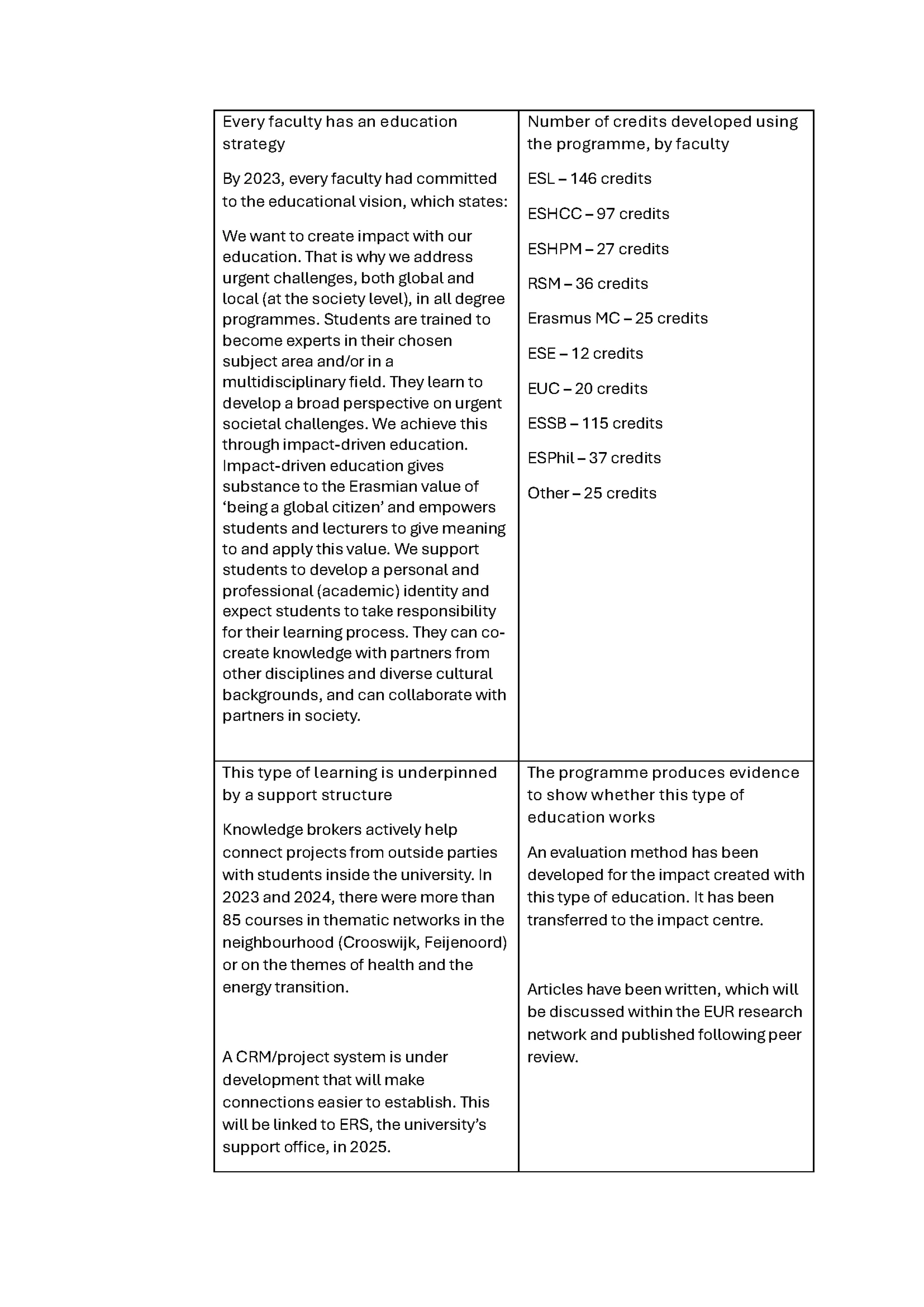

Objectives of Impact at the Core

In 2019, EUR formulated an ambition to create a positive impact in education. At the start of the associated university-wide programme, the initial situation of the faculties was defined on the basis of a wide-ranging survey. During a series of lectures, it was common for in-house or guest speakers to provide case studies to illustrate the theory that students were working on in tutorials or individually. In ESL and ESSB, it was common practice to present students with a structured version of practice, in accordance with the ‘problem-based learning’ model. Each programme had a single curriculum, based on realistic challenges developed with stakeholders as the foundation of teaching. All of these outcomes formed the starting point for the learning process and a theoretical exploration of how students could be better trained to make an impact on future issues.

Impact at the Core developed a model of ‘impact-driven’ education with representatives from the faculties, based on teaching models such as the Mezirow model (1996). Key goal: By 2024, every student in every degree programme will, at least once during their studies, work with direct stakeholders from outside the university on societal and/or transition issues, and this will be linked to sustainability issues where possible.

The objectives for students were:

- Understand topical, complex and difficult issues, in collaboration with stakeholders from the field and students from other disciplines.

- Be able to engage with different ways of seeing and thinking.

- Achieve the desired learning objectives, which are central to the curriculum.

The objective for lecturers and for the range of courses was:

- Develop a coherent teaching model by which this type of education can be delivered and students can be guided. The model should make it possible to apply the approach to course design, teaching approaches and forms of assessment, in line with EUR’s quality guidelines.

The objective around feasibility was:

- Design this impact-driven education to be affordable and feasible, taking into account high student numbers and lecturers’ workloads.

The objective with regard to the organisational and framework conditions was:

- Investigate and implement tools in the learning environment that support impact learning and ensure the quality of teaching. These must lead to a portal or digital system in which businesses/public authorities, lecturers and students can jointly engage in projects and lecturer professionalisation (development and provision).

The objective with regard to the innovation approach and developing a learning culture was:

- Learn together, drawing lessons from experience and formulating new goals through knowledge sharing and dialogues in a Community of Practice: bring together students and lecturers from different faculties to learn from the numerous experiments and provide lecturers with an opportunity for peer feedback.

What were the results?

The first phase, during the 2020–2023 academic years, consisted of experimenting and implementing several examples based on a ‘next-step’ innovation approach in different faculties and curricula. The team created an initial blueprint and visually showed how changes in education could create more space for realistic and ‘real-time’ issues. This in turn would enable students to develop skills that help them empathise, take a position and contribute to a way of seeing or solving a challenge. This raised questions like: Is it necessary to structure a problem beforehand? What should students be able to do by themselves? And where is guidance needed?

A teaching model was designed on the basis of the first 18 projects, which were carried out in almost all faculties and particularly focused on the Bachelor’s programmes. During this process, it was recommended that the number of experiments be increased and that ‘impact pathways’ be created. These pathways would allow Bachelor’s students to choose to build an academic professional profile focusing on engagement and impact with regard to complex, real-world issues. This choice is reflected in the selection of a minor and a specialisation; students prepare through standard skills courses and content-rich courses focusing on practice.

Although the ambition was to develop an impact-driven course for every programme, this was achieved for only 32% of the 39 programmes. Courses were developed for a total of 541 credits over four years. The focus was on developing courses for Bachelor’s programmes. Courses for Master’s programmes will be implemented during the redesign of Master’s programmes from 2025 onwards. Accordingly, the percentage of programmes that focus on solving challenging issues in consultation with external stakeholders is expected to increase by the end of 2025.

The programme developed a teaching model called a ‘learning landscape’, a knowledge base (‘toolbox’) and lecturer training courses to expand implementation from within the existing CLI structure. The programme worked with an active Community of Practice and will continue to do so within the CLI in 2025 and beyond.

In addition, the programme developed a number of concepts that could be used in new and existing degree programmes in the coming years, or be developed further:

- An ‘impact-driven education’ minor that closely follows the developed teaching model. Students formulate a challenge after discussions with stakeholders. Then, using a step-by-step model, they make a valuable contribution (insight, understanding, part of a solution). Learning objectives are linked to ILOs derived from the mandatory Dublin Descriptors.

- A model internship developed with ESL, ESPhil, ESSB and ESHCC.

- A model thesis assignment, developed with Esphil, suitable for a final project with a non-traditional graduation product that has a greater focus on practice. In 2025, as part of the institution-wide review of assessment policy, the ability to select new and different types of final projects will be included in the institution’s policies.

In June 2021, vice-deans of education from all faculties agreed to develop an ‘impact space’ pilot in the third year of Bachelor’s programmes. The aim in the third year of a Bachelor’s programme is to help students choose a societal challenge to work on during the minor and final project phase. In their final year, students then create a design or approach for an important societal challenge. This goal was worked on from 2022 onwards.

Gather challenges from the local area (KPI)

EUR gathers challenges from its local area. In 2021, two ‘impact education dialogues’ were organised, in which individuals from the university and civil society stakeholders talked about how students’ education could be better connected to society’s needs. The first dialogue focused on the healthcare domain and covered technology, ethics and interdisciplinarity, among other topics. Directors of healthcare institutions and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport stressed the importance of having students work on practical issues during their studies. In October, students from Health In Society (Gezondheid In De Samenleving, GIDS) at Erasmus MC led a discussion on technology in medical education.

Training for lecturers (KPI)

Together with the CLI, Impact at the Core developed a microlab, and a separate introduction to an impact-driven education webinar that was launched in 2021.

Easier collaborative learning with the outside world: a support system (KPI)

EUR was the first university in Europe to purchase a stakeholder platform to strengthen and facilitate collaboration within the learning environment between the university and the outside world. Following a pilot phase, this platform was rolled out in 2022.

Space for innovation: Erasmus X

The financial implementation x €1,000 (details shown under ‘Institutional and faculty-level summaries’).

| Erasmus X (x €1,000) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erasmus X | 53 | 859 | 1,006 | 1,264 | 2,164 | 2,071 | 7,417 |

Objectives of Erasmus X

The Erasmus X programme is designed to stimulate educational innovation to prepare the education area for 2050. In 2019, this programme did not exist, and educational innovations were a matter for individual courses or degree programmes.

In future-focused education, there are two key drivers for thinking about education, innovating and steering innovation: co-creation with multiple stakeholders and the responsible use of emerging technologies. In 2019, EUR formulated a mission to explore and design new ways of teaching using non-standard methods, in dialogue with students and other stakeholders. This assignment was given to Erasmus X. The programme encouraged an innovative approach that focused on experimenting with and testing new approaches. The experiments were based on teaching that matched students’ changing learning needs and the rapidly changing way we learn under the influence of technological development.

Erasmus X worked on innovations where there was considerable uncertainty around the ultimate impact or outcomes. For that reason, it was not expected that all projects would succeed, and not every experiment Erasmus X launched resulted in a follow-up project. The programme had three main goals: Ongoing development of EdTech and AI, design of complex innovations with external stakeholders and collaborative design with students, or co-creation.

What were the results?

Erasmus X fostered an innovative and learning culture in which experimentation, prototyping and testing are central. Its most significant achievements, listed below, will be built on from 2025 onwards.

From experimentation to scaling up

Even before the AI revolution took hold, Erasmus X was experimenting heavily with AI and EdTech. A concrete result of this experimentation is the AI minor now offered at EUR, Leiden University and Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). In addition, workshops for lecturers were developed to support the integration of AI education into daily practice. These initiatives will continue in 2025, as will the GenAI Communities of Practice, which support the integration of AI in education. In late 2024, the lessons learned were used to develop an institution-wide AI strategy, which from 2025 will focus on the responsible integration of AI into educational and other processes.

Complex innovation with multiple stakeholders

How do you design teaching that better reflects student diversity and the way students learn? To answer that question, Erasmus X developed a number of successful formats in collaboration with students, lecturers and external partners. They proved hugely successful, and will therefore continue in 2025 and beyond. In the area of accessibility, the most significant initiative was one introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, to create an online version of an introductory programme for students who are the first in their family to go to university. The pandemic was particularly challenging for this group of students. The numbers of students participating in the online learning environment multiplied. After the pandemic, the programme was converted to an on-campus version. Students are given practical tasks that help them get to know each other and become more familiar with the university and their personal challenges. The programme attracts hundreds of students every year.

Another innovation that emerged during the pandemic is the Minecraft Campus. This enabled students to interact within a gamified environment. During the pandemic, the Minecraft Campus played a crucial role in promoting social cohesion and community building. It led to new insights into future-proof learning formats, both virtual and in person, and collaboration with various internal and external stakeholders.

Soft skills alongside academic skills

In addition to academic knowledge, developing competencies and soft skills is essential for future-proof education. Erasmus X capitalised on this by encouraging competency-based learning. The ACE Yourself web app is a concrete example. It aims to support students during the transition from secondary school to higher education, and does so by developing non-academic and interpersonal skills and supporting metacognitive and reflective skills and self-regulation. The app was developed by four universities under the leadership of EUR, and is now being used within the Pre-Academic Programme and by a pilot group of secondary schools in Rotterdam.

Experiential learning at the hub in South Rotterdam

One of the most impactful Erasmus X initiatives was the creation of a youth hub (the ‘Hefhouse’) in South Rotterdam. In collaboration with residents and neighbourhood representatives, a community centre was set up where researchers, lecturers and students from senior secondary vocational, higher professional and academic education could work together on practical issues. More than 600 students worked on projects focusing on societal challenges in areas such as youth issues, health care and education. The initiative offered students the chance to immediately put their academic knowledge into practice, while the neighbourhood benefited from innovative solutions.

Developing an innovative culture

An innovative organisational culture is crucial for successful educational innovations. The programme encouraged such a culture by creating spaces for experimentation that were both physically and mentally safe. A key initiative was the ‘Fail Fast Forward’ workshop series, which encouraged students and lecturers to see failure as an essential part of the learning process. Five of these workshops were organised in 2021; from 2022, they became a monthly initiative in various faculties. In addition, a failure/resiliency track aimed at training tutors and study advisors to guide students to handle failure and develop resilience was developed in collaboration with ESL and EUC.

A safe experimentation environment for emerging technologies such as AI was also one of the priorities of the programme. At the initiative of the IT Department and other internal partners, we looked at developing a secure testing environment where responsible experimentation with AI could take place. This contributed to a culture that embraces innovation and gives students and lecturers the space to explore new technologies safely and responsibly.

In addition, strategic foresight was used in collaboration with SURF to explore future developments and embed innovation sustainably in the AI strategy for education.

The flagship projects that were developed will form the basis for structural changes to be built on in the years ahead. The combination of co-creation, human-centred technology and an open innovation culture will ensure that the area of education is prepared not only for the challenges of today, but also for the challenges of the future.

Findings of the Supervisory Board and University Council

Findings of the Supervisory Board

Through its Quality Committee, the Supervisory Board takes note of, oversees and acts as a sounding board for developments that serve to strengthen the quality of education and research at EUR.

In 2024, it was involved in the implementation of the educational vision 2023, in conjunction with the development of the EUR Strategy 2025–2030, which was also a follow-up to the mid-term review of the Quality Agreements in 2022. The Quality Committee was very pleased with the educational vision and recommended that external perspectives be embraced in this process.

A focus of the Quality Committee, which had already been included in the 2023 Annual Report, was the ongoing development of the internal quality assurance system. The Quality Committee noted that solid progress had been made and was pleased that this will be an ongoing process, ensuring constant attention to quality assurance and preparation for the Institutional Quality Assurance Audit. The Quality Committee recommended using the panel discussion as a catalyst for the process within EUR.

One of the major developments affecting educational quality is the Smarter Academic Year project. The Quality Committee agrees with the new range of 28 to 32 weeks. It also understands the decision to maintain the ‘Nominal is Normal’ policy for now, partly in light of developments, but also supports a critical look at the compensation and exception rules.

The Research Vision was also addressed. The Quality Committee particularly appreciates the way this process unfolded, with many parties being involved. The Quality Committee agrees with the direction, but calls attention to the unique profile of EUR.

The Quality Committee agrees with the moves EUR is making in terms of education and research quality. The committee notes that the findings from 2023 have been accepted and acted upon and feels involved and informed about developments at EUR in the area of quality assurance. The Quality Committee looks forward with interest to further developments and implementations in 2025, and is confident that the areas for improvement identified and raised in 2024 will be addressed.

Findings of the University Council

This document serves as a reflection of the University Council’s Higher Education Quality Agreements (Kwaliteitsafspraken Hoger Onderwijs, HOKA) working group regarding HOKA investments over the past six years. The University Council wrote this reflection in the context of the final evaluation of the HOKA investments, which is being conducted throughout the university. It is important to note that this reflection was written by the current members of the HOKA working group. These members have only been actively involved in HOKA for a few years, and thus were not involved in the preparation of HOKA’s spending plans or in the first few years of implementation. Nevertheless, they have a good understanding of HOKA-related developments over the years. They gained this understanding through conversations with current and former colleagues, by studying plans and past reviews and by questioning the various teams that implemented the HOKA plans.

This reflection has three parts. The first part is a brief discussion of the projects that collaborated with the HOKA working group (Student Wellbeing, Impact at the Core, Erasmus X and Community for Learning & Innovation). Part 2 is an explanation of how the working group perceives some of the experiences with HOKA of other participating bodies at the faculty and programme level. Finally, we provide a conclusion and overall reflection on the entire HOKA programme.

Individual programmes

Student Wellbeing

During the HOKA period, a delegation from the University Council met with the Student Wellbeing project team around twice a month. Communication was always clear, with timely updates on projects and adequate and prompt responses to queries. The representatives felt that their input and feedback were highly valued. Even now, in the transition phase, the Student Wellbeing team is actively soliciting input to help make the programme as valuable as possible.

Over the past few years, the Student Wellbeing team, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, has constantly sought and found ways to improve the wellbeing of students at EUR. This included continuous evaluation of the success of the initiatives, allowing active choices to be made regarding the continuation of such initiatives as well as possible innovations. An important step was the Student Wellbeing Manifesto, which created a shared, holistic vision of student wellbeing at EUR. The manifesto was signed by the Rector Magnificus of the time and by the deans, and all staff and students can also sign it (https:/ www.eur.nl/onderwijs/studeren- rotterdam/studentenwelzijn/over-ons/studentenwelzijnsmanifest).

In recent years, the Student Wellbeing team set up an integrated programme to offer the most diverse programme possible to increase student wellbeing from many different perspectives. Various online products were created, sometimes in collaboration with other universities. One is the Student Wellbeing platform (https:/www.eur.nl/en/education/study-rotterdam/student-wellbeing), where students can interactively search for the form of help most suited to their problem. There is also the newly developed ROOM app (https:/my.eur.nl/nl/eur/onderwijs/student-wellbeing-platform/room-grow) and the collaboration within Caring Universities, in which students can engage with online programmes to increase their wellbeing (https:/moodlift.nl/). These are easily accessible initiatives that enhance student wellbeing.

The Student Wellbeing team has also introduced a number of offline initiatives to help students, such as the Living Room, which has proven extremely successful. This is a physical location in one of the university buildings, where students can meet each other or talk to trained student hosts to get wellbeing support. In addition, the Personal Support Hub (PSH), adjacent to the Living Room, was set up to offer targeted help on specific themes, such as substance abuse. This is often done in collaboration with healthcare professionals and other experts. It is also worth mentioning the efforts of the Student Wellbeing team in the area of physical wellbeing and the effect of exercise on wellbeing. An example is the various Sport & Skills pathways, which are widely used by students.

Around twice a year, the Student Wellbeing team organises a Wellbeing Week, during which they run various activities for EUR students. During these weeks, students are introduced to Student Wellbeing in an accessible way and can immediately acquire new knowledge and skills. These efforts have been recognised by other universities, which have contacted EUR’s Student Wellbeing team for advice and suggestions.

EUR staff are included in the student wellbeing process. For instance, Student Wellbeing Officers (SWOs) were appointed in every faculty last year. The SWOs are a point of contact for faculty staff, with the aim of ensuring the implementation of Student Wellbeing initiatives at the faculty level. The SWOs from the various faculties attend central meetings led by the Student Wellbeing team, to exchange knowledge and expertise with the goal of maximising student wellbeing within and across all faculties. Working together in a coordinated way with central leadership reduces fragmentation. In addition, lecturers are offered Student Wellbeing training, which provides them with appropriate information on discussing Student Wellbeing with students, identifying problems and referring students to appropriate resources if necessary.

An important part of the programme was monitoring and conducting research relating to the Student Wellbeing initiatives. This allowed questions from stakeholders, including the participation bodies, to be answered, and allowed adjustments to be made where necessary. For example, the programme looked at campaigns to reduce substance use among students. Because the Student Wellbeing team collected and used data, targeted and meaningful campaigns to improve mental wellbeing were able to be developed.

Impact at the Core

A great deal was achieved within the Impact at the Core project. Although not all faculties were equally enthusiastic and interested at the outset, educational innovations were eventually initiated in programmes within all faculties at EUR. These innovations covered a wide range of ways for students to work on topical and challenging problems in modern society. In addition, through workshops and other meetings, the project team connected with members of the Erasmus community who were interested in creating an impact. During these meetings, participants were informed about innovations, but were also asked for their own ideas. This encouraged engagement and enabled co-creation. Furthermore, important practical matters were arranged to facilitate the involvement of external stakeholders, such as the collaboration with Erasmus Connects and the launch of the Riipen work-integrated learning platform, which allowed ‘wicked problems’ from external stakeholders to be brought into the curriculum. The fact that EUR was the first university in continental Europe to use Riipen illustrates both the vision and the determination of the Impact at the Core team and places our university at the forefront of developing this type of education.

The University Council is satisfied with the way it was involved in the project. HOKA taskforce members received regular updates on the project. Discussions on the project were open with plenty of space for the Council to ask critical questions, express opinions and suggest ideas. Looking back, we would like to make the following observations.

- The project was successful in supporting faculties through its learning innovators and project staff. As there was growing demand for such support, the capacity to provide support was limited, and not easy to increase in the current labour market. This obviously affected the number of educational innovations that were able to be successfully implemented.

- Although all faculties eventually launched educational innovations under the Impact at the Core project, not all faculties were equally engaged. Ideally, all faculties would have made a clear commitment to the project and been willing to share experiences and ideas. This is the only way to ensure that projects have an EUR-wide impact in the long term.

- The workshops and other meetings attracted relatively few students, and their perspectives may not have been sufficiently incorporated in the development of innovations. More student involvement could have increased the effectiveness of the overall project.

- There was (and is) potential to link impact education more closely with other current developments at our university, such as Convergence (a collaboration between EUR, Erasmus MC and TU Delft), which is important for efficiency and effectiveness reasons.

- Proper testing of impact-driven education is a challenge in itself, requiring tools and lecturer training.

- Evaluation of the effectiveness of the various innovations should be based (among other things) on sound academic research. For several reasons, including the fact that it was difficult to attract suitable researchers, the project was not very successful in achieving this goal.

Erasmus X

Over the past few years, the University Council has regularly evaluated the functioning and development of Erasmus X. These evaluations have revealed both strengths and weaknesses. Overall, the experience of collaborating with the Erasmus X team was positive. Communication was mostly clear and constructive, allowing for critical questions and the exchange of ideas. However, over the years, we noticed that budgets and relevant documents were sometimes delivered late, complicating the evaluation process. Fortunately, a noticeable improvement has been made.

Erasmus X has produced a number of successful projects, such as the ‘Ace Your Self-Study’ app, which was effective in helping improve the study skills of first-year students. Projects such as ‘Online Virtual Campus’ and ‘Redefining the Classroom’, which connect students with societal challenges, also show that Erasmus X has played a valuable role in educational innovation within the university. Moreover, Erasmus X has supported both students and staff in using AI, which aligns with EUR’s future-focused vision.

However, a key concern remains the monitoring and evaluation of the long-term impact of projects. Monitoring of the implementation phase was inadequate, resulting in some initiatives not being sustainably integrated into mainstream education. There were also initiatives that proved less than successful, which is partly inherent in the innovative nature of Erasmus X.

Once HOKA is wrapped up, Erasmus X will be included in the administrative agreements, since it is essential to retain the knowledge and experience gained and to build on the initiatives that have proven successful. The University Council emphasises the importance of safeguarding this knowledge to sustainably retain valuable educational innovations within EUR.

Community for Learning & Innovation

Over the past six years, HOKA funds have been invested in various educational innovations at EUR. One of the main initiatives made possible with these funds was the Community for Learning & Innovation (CLI). With the HOKA funds expiring in 2025, the CLI will be structurally incorporated into the university. Funding sources will include the Administrative Agreement funds, which are intended for educational innovation.

Since its creation in 2017, the CLI has developed into a major player in educational innovation. In collaboration with faculties, lecturers and students, the CLI has promoted digital learning environments, educational training courses and knowledge sharing through initiatives such as Communities of Practice and EdUnconnect. The focus on professional development, educational careers and digital learning tools will remain a focus beyond 2025.

The University Council found its collaboration with the CLI extremely valuable. Since 2023, the CLI and the University Council’s HOKA taskforce have held active discussions every two months to discuss the CLI’s activities and any questions, concerns or comments. These initiatives have been well received by both parties and have led to a desire to work even more closely together. For example, the CLI can now consult with or involve a member of the HOKA taskforce when considering new innovation projects.

This closer collaboration highlights the transparency in communication and the CLI’s willingness to incorporate input from students and staff, which is considered a positive development. At the same time, it is important that the CLI not only plays a supportive role, but also actively meets the specific educational needs of students and lecturers. Structurally embedding the CLI will provide opportunities, but requires a clear strategy for maintaining and strengthening community involvement.

Other participation bodies

HOKA-related procedures for participation vary from faculty to faculty. During a survey in 2021, it was noticed that small faculties had a more bottom-up approach to the co-creation and monitoring of plans. The participation bodies in larger faculties experienced a less aligned and more bureaucratic process with regard to HOKA matters. Representatives from these bodies reported that although some plans were very well structured and organised, there was little room for co-creation or providing feedback to the faculty board on the various projects. They also struggled with a common HOKA problem: defining success within the framework of these investments. For students in particular, it was often difficult to understand how HOKA improved the quality of education and how the impact of HOKA could be measured. This was compounded by the fact that students often serve on programme committees and faculty advisory boards for only a year, which means knowledge of rules and procedures is often lost when they leave.

In response to the above findings, the University Council made several recommendations to the faculty participation bodies in 2021. The first recommendation was to create a handover guide for new members of these bodies. The second recommendation was to set up a group to work on HOKA projects. This would enable faculty advisory boards and programme committees to have people specialising in HOKA matters and get a deeper insight of what was happening with the projects. Thirdly, the University Council recommended that training be given to raise awareness of the rights of participation bodies with regard to HOKA. Finally, it was pointed out that it could be useful to hold discussions on HOKA matters with other participation bodies. The University Council took the initiative, and organised a number of meetings for the faculty participation bodies.

Although not all participation bodies followed the recommendations, in 2025, some representatives reported that they felt better equipped to deal with HOKA-related challenges because of the joint meetings. A number of decentralised participation bodies indicated that they made some deliberate choices relating to the HOKA funds; for example, less or no co-creation at that level. They often became more critical and proactive in relation to HOKA matters. As a result, initiatives were taken by the boards in some faculties to better involve participation bodies in plan development.

Conclusion and overall reflection

In conclusion, the Council would like to raise certain concerns that are also relevant to the continuation of the programmes under the new Administrative Agreement funds. Firstly, it is notable that it remains a challenge to obtain input from students regarding the design and implementation of the various programmes. This applies at both the central and decentralised levels. Secondly, it is sometimes difficult to get a clear picture of the measurable effects of educational innovations and their possible applications in teaching practice. Thirdly, the Council would have liked to have had greater insight into the deployment and effectiveness of Learning Innovators in the various faculties.

Despite these concerns, the Council looks back on a productive period of collaboration between the University Council and the various HOKA umbrella projects that gradually took shape between 2019 and 2024. During this period, continuity among the staff and student members of the Council was ensured as much as possible with good handovers from year to year, and not least through the valuable guidance of a single, permanent point of contact and intermediary between the Council, the various central HOKA projects and the CLI.